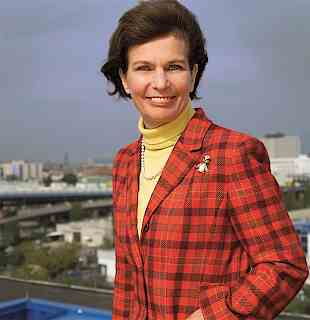

Heidi Senger-Weiss in conversation

Making intuition pay

Issues

Text

Pictures

Gebrüder Weiss

Tags

Heidi Senger-Weiss in conversation with Frank Haas: on rootedness and openness, instinct and reason.

Gebrüder Weiss is viewed as the world's oldest transport company. Does this long tradition make you proud?

Of course. It's very unusual for one generation after the other to follow in the footsteps of their predecessors, and to find professional fulfilment in the same challenge. And we haven't just established a bond with our industry, but with our region too. In the 500 years since our company was established, we have only moved our headquarters by 30 km. We have developed our strengths in this region and grown roots here, but still remained open to the world beyond.

When you and your husband began managing the company's operations in 1968, it marked a watershed. For the first time a woman had taken over the reins of this tradition-laden company, and that at a time when women still needed their husbands' permission to open a bank account.

The issue with the bank account didn't bother me as much, but I even needed my husband's permission to include my children, the children I had born, on my passport. That was how things were back then. If I had had a brother, my life would have been very different. But I was my father's only child and the last member of the family to bear his name. And there was no other shareholder who could have run the company as a general partnership. So they decided to try their luck with this young, 27-year-old girl.

How did the employees respond? Did they believe you could cope?

The employees were happy and grateful that I took over, because otherwise the company would have been sold to some big corporation. They also gave me their full support from day one, even if they didn't always think I knew what I was doing. That's understandable. I had no experience of the job whatsoever. My father died when he was 66 and the venerable Gebrüder Weiss management team was aged between 63 and 70 when my husband and I started out. The first thing we did was to bring in a new generation. And within three years, the management staff at the subsidiaries and branches were all between 40 and 45. That proved a real boon for Gebrüder Weiss (laughs).

Heidegunde Senger-Weiss was born in Vienna on 20 May 1941. After finishing school in the town of Bregenz, she attended the Vienna Academy of International Trade. Following internships in Switzerland, the Netherlands and the US, she joined Gebrüder Weiss in Vienna as the assistant to the branch director. In 1968 she and Paul Senger-Weiss took over the reins at Gebrüder Weiss with its 1000 employees in Austria and a branch in Hamburg. In 1969 they both joined the Management Board. They have three children: Wolfram (born in 1971), Elisabeth (1972) and Heinz (1974). In 2005 Heidi Senger-Weiss joined the Supervisory Board where she is currently chair. Her sons Wolfram and Heinz are now members of the Management Board.

Heidegunde Senger-Weiss was born in Vienna on 20 May 1941. After finishing school in the town of Bregenz, she attended the Vienna Academy of International Trade. Following internships in Switzerland, the Netherlands and the US, she joined Gebrüder Weiss in Vienna as the assistant to the branch director. In 1968 she and Paul Senger-Weiss took over the reins at Gebrüder Weiss with its 1000 employees in Austria and a branch in Hamburg. In 1969 they both joined the Management Board. They have three children: Wolfram (born in 1971), Elisabeth (1972) and Heinz (1974). In 2005 Heidi Senger-Weiss joined the Supervisory Board where she is currently chair. Her sons Wolfram and Heinz are now members of the Management Board.

What gave you the confidence to take such tough decisions?

It was born of necessity. And everybody understood that somebody aged 68 or 70 needed to hand over control of the local offices to someone younger. Of course not everybody was happy, but we didn't face major resistance from the old guard, partly because we always treated them fairly. The innovation push was important at that time, not least in areas like establishing direct truck routes on an international scale.

To what extent did your management style differ from your father's?

Completely, I'd say. I joined the company at the end of 1965, two years before his death, and I know that he was already tired and worn out. He'd taken over the helm in 1921, when he was just 19 years old. That was an incredibly difficult time and he mastered the challenges magnificently. After World War II, when we had hardly any capital left, he basically rebuilt everything from the ground up. So the company we assumed control of already had solid foundations, and a network of branches that extended nearly throughout Austria. But he wouldn't have wanted to start over yet again.

Did you have any other role models or modern theories that helped to guide you?

I'd tend to say it was instinct and the urge to do as well as humanly possible. I may have studied international trade but all these theories of management were still really vague back then. Everyone has strengths and weaknesses. I'd say that my strength lay in motivating colleagues. I could build good relationships with them and secure their commitment to the company. As a consequence, we didn't have much fluctuation in our workforce. Instead we had a lot of enthusiastic team players. At the same time, I never thought of myself as being some kind of superior forwarding agent. The people who learned the trade from the bottom up, they were all much better, and I was happy to accept that. I did different things. And, in my husband, I had a great partner whose skillset complemented mine really well. Together we usually ended up taking the right decisions. I would never have managed that alone.

Did this professional partnership ever put a strain on your home life?

Each of us had our own portfolio, something we were chiefly responsible for. Both in the company and at home. And we substituted for each other if one of us was sidelined for some reason. During the first years I gave birth to three children, so my husband had to shoulder a lot of the burden. As a mother, you can't look after your family alone if you are also running a company. So each of us always needed the other and we had mutual respect for each other.

Did you have to draw up new rules for keeping your personal and professional lives separate?

We always tried to avoid doing one thing when our children were present: discuss the company's problems. Managers devote very little time to things that are running well. They register a sense of satisfaction and then move on to something else. On the other hand, they are constantly pre-occupied with problems: "I lost another customer or partner ... a competitor undercut me ... an employee handed in his notice." And then they are surprised that the next generation says: "No, I don't want to take over the company."

What would your father say, if he were to return here for a day and see all the things that have happened?

Well, he'd certainly get a shock if he saw the new head offices ...

I suppose that – just like you – he would be a bit turned off by the green furniture, wouldn't he?

(Laughs) That's one example. We owe the colour orange to him. At the time, that was incredibly innovative. All of the other trucks were mouse-grey or black. My father was the first person with the courage to paint the trucks a different colour.

But wasn't that just a mistake at first? It was the colour of the anti-rust paint.

Yes, it was the anti-rust paint on a truck that wasn't really ready but needed to be used. When my father saw it, he said: "Super, you can see that from a mile off! That's the colour we'll use for our trucks." To stop it from standing out too much, he initially retained the grey tarpaulins, and later they tried blue tarps. But the truck itself always stayed orange. That would definitely make him happy, the fact that we still show our colours in orange.

Conversely, was there any event in the company's history that you would have liked to witness personally?

Certainly, there are a whole range of things, for example in 1781 when my ancestor Johann Kasimir Weiss was invited to become a partner in the Fussach trading post, one of the companies that ultimately became part of Gebrüder Weiss as we know it today. The brother of the owner had gone bankrupt following a bad investment and evidently needed some capital. As a result, our family acquired a 50 per cent share, even at that early date. The oldest son in the family, Josef Weiss, then married wisely and became the co-owner's son-in-law. So the entire firm ended up in the Weiss family's possession. Those must have been exciting times.

And what advice would the Frau Senger-Weiss of today give to the Frau Senger-Weiss of 1968?

To be honest: back then my health started to suffer. The responsibility I suddenly had to bear, it was all a bit too much for me. So I would have advised the Heidi Weiss from back then to take things easy. And to learn to accept that erring is human. The only important thing is that the sum of the errors is significantly less than the sum of the correct decisions. But when you are starting out from scratch, you get incredibly uptight about making mistakes. And that takes its toll.

When taking decisions, did you generally follow logic or gut instinct?

I'm a woman. And most women are pretty keyed to their emotions. When I have taken decisions I didn't feel comfortable with, they usually turned out to be wrong. But there are, of course, people who base all their decisions on reason and logic.

Your ancestors' core business, the courier service running between Lindau and Milan, was gruelling and very dangerous. Was any code of conduct ever drawn up as a result?

Most certainly. Our values today derive straight from them. For example, our willingness to take risks. In October my husband and I hiked along the key section of the Milan Courier route – from Thusis down to Isola. There are three gorges on this stretch: the Via Mala, the Roffla Gorge and the Cardinell. Not to mention the Splügen Pass at an elevation of 2,100 metres. We made it in three days. By contrast the Milan Courier only needed two and a half. But we weren’t carrying a load. We didn't have to guide any mules, and we had wonderful weather. Back then, that job was considered extremely risky and it carried a great responsibility. The couriers had to pay high deposits to cover damage en route. They were fully responsible for their merchandise. If a mule slipped and its load fell into a ravine, they often climbed down to try and retrieve it. What's more, they had to speak different languages, e.g. Swiss German and Italian; they had to be familiar with the customs procedures, and they needed to be skilled and know how to negotiate borders smoothly. Those are all things that we still face today.

And despite the challengers, your ancestors always persuaded their offspring to take over the company. What motivated people back then?

Partly the fact that it was simply a great job! The courier descends into Milan and enters a whole new world – coming from this small village of Fussach and arriving in the heart of a global capital! Maybe he got to bring home oranges, or silk goods. And he could see and hear what was going on around the Mediterranean. Then he heads back and tells everyone about his exploits at the local inn. That's incomparably more exciting than if you are running a farm and have the occasional newborn calf to report. Nothing against rural life, but being a courier was something really exciting. And this enthusiasm for "moving things" proved infectious. The next generation started out as assistants, then became deputies, and finally they assumed responsibility themselves.

So, broadly speaking, the job was always a great adventure?

It really was an adventure. But above all our family is moved by the spirit of mobility. And for that you need to be open to other cultures. Being grounded and level-headed is fine, but a cart driver who was openly proud of his mobility, had to have a cosmopolitan outlook and be receptive to other influences and cultures, so that he could return home with them and say: "Listen here, I experienced something fantastic!" If you are prepared to respect others and don't always assume you are best in everything, you can pick up a lot of positive ideas. But that again has nothing to do with tradition.

Actually, it does.

In any case, the feeling of having roots in a certain place is very important to me. Of knowing where I belong, where my home is. And that, in turn, allows me to be open and innovative as well. Just take a look at the large, successful family companies in the Vorarlberg region. They have both: they have strong roots in the area, yet their reach extends all over the world. And that's a gift that we have always possessed at Gebrüder Weiss. And hopefully it's something that won't ever change. I hope that we can remain attached to our roots while having the initiative to chart new territory. Of course, we won't be trying experiments that are risky enough to jeopardise the whole company. But we need to remain courageous and accepting of new things. Even if we can't be sure that every experiment will prove a success.

Frank Haas is head of brand strategy and communication at Gebrüder Weiss and editor-in-chief of Atlas.